SPARS during World War II

.

| In the beginning, the Navy, Marine Corps and

Coast Guard pooled their available facilities and staff to train women

together. Thus, Coast Guard reserve women were recruited by the Office

of Naval Officer Procurement and trained in naval schools already instructing

new WAVES.

By July 1943, the SPARS had their own recruiters

working in all District Coast Guard Offices.

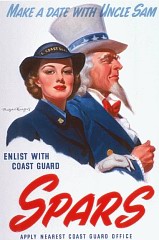

Right: Early SPARS Recruitment

Poster asking for application at the nearest office of Naval Officer

Procurement. |

.v |

|

.

The actual recruiting campaign for SPARS began

in December 1942, and the first members (15 WAVES officers and 153 enlisted

WAVES) were selected directly from the Navy and transferred into

the Coast Guard. Many of the initial SPAR officers were assigned to Naval

Officer Procurement centers, where they coordinated recruiting and public

relations drives.

.

| Unlike the other armed forces, however, the

Coast Guard wanted a particular type of woman. The ideal recruit had to

possess outstanding athletic fitness, especially with regard to swimming

capability, have solid nautical knowledge (with sailing or yachting experience

preferred), and share the abolitionist Northeast tradition that appealed

to the New England-centered, maritime-rich Coast Guard tradition. However,

in keeping with American spirit, the upward pathway for social advancement

was based on merit for any women with maritime traits, even the daughters

of ordinary fishermen. |

.. |

Swimming Training of SPARS

Swimming Training of SPARS

|

.

|

v |

It was not easy to find women steeped in maritime

heritage, correct philosophy toward open racial acceptance, and practical

expertise in sea lore.

Recruiters were also hampered by:

(a) the high wages paid by war

industries to women workers;

(b) the recruiting limitations

of the War Manpower Commission and Office of War Information, which disallowed

enlistment of critically needed women,

(c) parental and boyfriend objections,

(d) the hesitation of independent-minded

women to accept military lifestyles,

(e) the fear of being sent to

distant assignments in unknown areas

(f) the attitude of many women

- especially in the most-desired yachting and sailboat social circles --

that wartime sacrifice was not worth their personal time or effort, especially

if their social activities were curtailed. |

.

| The Coast Guard under Dorothy Stratton rose

to the challenge of gaining these desired women. It even opened its Coast

Guard Training Station for enlisted SPARS at a ritzy Palm Beach hotel,

so that recruiting promises could include basic training under glamorous

Florida seaside conditions. Captain Stratton was thus able to achieve her

goal of enlisting and appointing the exact type of athletic and nautical-savvy

Coast Guard women most sought after. |

.. |

Morning calisthenics of

SPARS at the training center in Palm Beach

Morning calisthenics of

SPARS at the training center in Palm Beach

|

.

Commencing on 1 July 1943, in view of jealous

Navy competition for the "best girls," the Coast Guard separated its facilities

and strictly recruited and trained its own women. The Coast Guard reserve

recruits were medically examined by another Coast Guard gem of elite female

companionship -- the nurses and female doctors of the commissioned corps

of the Public Health Service. Under Captain Stratton, the Coast Guard reservoir

of ideally capable womanpower was enthusiastically filled.

.

|

.v |

SPARS contingent in dress uniforms

march behind their officers and petty officers through Washington, DC,

during World War II.

All are expert swimmers and accomplished

nautical experts. |

.

| SPARS women mainly replaced men

in shore stations working in traditional clerical

and routine services. As the war progressed,

Coast Guard women were placed in charge of greater areas of previously

male-only control.

For example, a small group of SPARS worked

in the field of Coast Guard aviation as parachute riggers, link trainer

operators, aviation machinists' mates and air control tower operators.

Others worked as radio technicians, gunners' mates or radarmen. |

..v |

Aircraft maintenance by

SPARS

Aircraft maintenance by

SPARS

|

.

Captain Dorothy C. Stratton

Captain Dorothy C. Stratton

|

..v |

In December 1943, some of the limitations

on rank for women of the Coast Guard Reserve were removed by Congress to

enable greater contributions by SPARS in the war effort.

Lieutenant Commander Stratton was promoted

to Captain, which became the highest rank authorized for a SPAR officer.

Captain Stratton remained Director of the SPARS until September 1945. The

second Director of the SPARS became Captain Helen Schleman. |

.

| The first SPARS were assigned to overseas

duties in Hawaii and Alaska in September 1944 because of a basic Reserve

Act amendment that removed restrictions where SPARS could serve.

Both were important duty stations and many

SPARS eventually served in both places. |

.v |

SPARS leaving for Hawaii

SPARS leaving for Hawaii

|

.

Olivia Hooker and Aileen Anita

Cooks on the ladder of the dry-land ship USS Nerversail during their

"boot" training

Olivia Hooker and Aileen Anita

Cooks on the ladder of the dry-land ship USS Nerversail during their

"boot" training

|

.v |

In October 1944, Afro-American women were allowed to enlist as SPARS,

provided they were fully qualified. Since the officer training program

for recruited civilians had already stopped, Black women were barred from

becoming officers directly from civilian life (the previous officer source

of many white women).

Four Black women were accepted into the SPARS during the first six

months that enlistment was opened to them. Although the officer training

was closed for any female civilians, it was possible to apply as officer

candidate and attend officer training for prior-enlisted SPARS (including

black enlisted SPARS). A few black women enlistees were commissioned as

ensigns before the end of the war. |

.

| Most members of the SPARS were very young

women. According to a survey from May 1943, the average age of enlisted

SPARS was between twenty-two and twenty-three. More than half of the enlisted

personnel were under 25 years old and nearly 90 percent under thirty. More

than 66 percent had graduated from high school and most of them had worked

for more than three years in a clerical or sales job. A large number of

women came from Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio or

California. |

.v |

|

.

Ensign Mary C. Lyne, USCGR (W)

employed in the Office of Naval

Procurement in Washington, D.C. |

.v |

A similar survey from July 1943, regarding

SPARS officers, showed that the average SPAR officer was about 29 years

old. Only 10 percent of the SPARS officers were over forty.

Nearly all had graduated from college, a third

had even done some graduate work and 20 percent had earned master's degrees.

Most of them had worked for about seven years in either a professional

or a managerial position in the field of education or government. |

.

SPARS women contributed greatly to Coast Guard

management of all shore-based phases of the war effort. They conducted

various Coast Guard tasks in support of military readiness, assistance,

marine safety and law enforcement.

SPARS training marksmanship

... just in case

SPARS training marksmanship

... just in case

|

.v |

Their successful performance of vital administrative

and organizational functions extended their duty from purely clerical and

administrative tasks, as first envisioned, to the most important port security,

logistical and administrative jobs by war's end.

Known as the "women behind the men behind the

guns," female participation insured Coast Guard proficiency across the

Seven Seas during World War II. |

.

.

[ I. Development ]..[

II. Facts about the SPARS ]..[

III. Uniforms ]..[

IV. Sources ]

|